Focusing on the Vulnerable in Dorothea Lange’s Photographs

Maddie Pintoff

At the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), there is an exhibit titled Words and Pictures featuring photographs taken by Dorothea Lange (1895-1965). Although Lange began her career taking portraits of San Francisco’s social elite, when the Great Depression reduced her business, she became interested in photographing ordinary people who were suffering in hard economic times (Whitney). Each of Lange’s pictures featured in this exhibit take people as their subject, but they are not the important or wealthy people so often captured in portraits; instead, they are ordinary people, including farmers, lawyers, migrant workers, and mothers. Lange has many photos that portray children, often capturing their relationship with their parents and focusing on their vulnerability. Lange so artfully encapsulates various people's lives in a single frame that viewers can almost see the story behind each (“Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures”). She accomplishes this not just with her images, but also with the words she chooses to “fortify” her photographs (Bullock). Lange used her portraits to help draw attention to important issues ranging from widespread suffering during the Great Depression to the effects of World War II on everyday life to the role of the public defender in the justice system (Bullock). In her photographs "Child and her Mother, Wapato, Yakima Valley, Washington. August 1939," "Mother and Child, San Francisco, 1952," and "The Public Defender, Alameda County Courthouse, California. 1955-57," Lange captures images of people in vulnerable situations and seems to ask her viewers “who matters?” Her composition choices pose questions and draw in the viewer’s emotional response in ways that insist ordinary people matter.

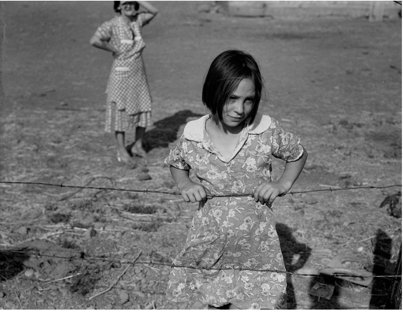

Figure 1. Child and Her Mother, Wapato, Yakima Valley, Washington. August 1939.

In Child and her Mother, Wapato, Yakima Valley, Washington. August 1939, Lange photographed Lois Adolf, who was 10 at the time, with her mother in the background (Figure 1). The Adolf family lived in the Yakima Valley of Washington, an area hit hard by the Depression (Whitney). Lois's expression is forlorn, with her eyes downcast away from the camera. In the background, her mother, slightly out of focus, raises a hand to shield her eyes from the sun, squinting in the direction of the viewer. Lange took at least eight photographs of the pair, but this particular one was her favorite (Meister). It was probably due to the emotional heaviness conveyed by this seemingly simple photography: from Lois' expression, to the barbed wire in front of her, to the desolate land behind them. In addition, the mother’s pose conveys a sense of worry as she hovers behind her child, watching with concern. These photographs were taken while Lange was working for the U.S. Government, and their purpose was to help draw attention to the need to aid farmers and migrants (Meister). Children, to most people, are weapons of sympathy. Given that people love children and do not want them to suffer, what better a subject to be used for Lange’s appeal for help, than a dejected child in a desolate space?

Lange was purposefully using Child and her Mother to express a narrative, much like Clark discusses in Las Meninas. Clark believed that every aspect of a picture contributed to its story, from the positions of the people to the colors of the painting. Clark speaks of this "network of relationships" between characters, and how "their disposition, which seems so natural" gives the painting a new layer of depth and reality (5). The same analysis can be applied to Lange's photography. Lois' expression particularly impacts both the narrative told and viewers’ feelings on the subject. Her downfallen expression evokes a feeling of pity, or sorrow for the girl; the relationship between the daughter and watchful mother symbolizes the worry viewers are drawn in to share.

Figure 1A. Child and Her Mother (2), Wapato, Yakima Valley, Washington. August 1939.

Others have pointed out that as a photojournalist, Lange “blurred the line between reportage and fine art,” because she was “an artist under the guise of a journalist and an activist under the guise of a dispassionate civil servant” (Gregory). This part of Lange’s role, where she captures what she sees, but frames it in a way to elicit a particular viewpoint and emotional response, seems to illustrate Wilde’s point that “lying … is the proper aim of art” (3). Even Child and her Mother (Figure 1), which at first seems only to capture what is in front of Lange’s lens, betrays a partial deception in order to manipulate viewers’ sympathy. In this series of mother and child, there is a second photo of the two in which Lois is looking to the side, a shy smile on her face (Figure 1A). Her mother still stands in the background, with the same pose. But in this second photograph, the viewer gets a different feeling from the picture: it seems lighter somehow, and less depressing. Lois' expression leads the viewer to start thinking about mischief, instead of how farmers and their families are suffering due to the Great Depression.

Figure 2. Mother and Child, San Francisco. 1952.

A later photograph by Lange also depicts a vulnerable child, this time on a walk with his mother. Unlike the first image, which features a desolate and depressed setting, Lange’s 1952 Mother and Child, San Francisco is set in a city and stores as well as cars can be seen in the background (Figure 2). The core focus is on the mother and child walking; the viewer seems right there with them, as though passing them on that same sidewalk. The mother's gaze flicks lazily to the camera, as if it were something that just happened to catch her gaze as she was walking. The child behind her wears a coat, a tad too large for him, as he walks, head down. He appears to be very little, maybe as young as three. The mother looks like a serious person; she wears dark clothes and is extremely well put together. Maybe she is strict. She seems to be a distant mother, since a more nurturing and loving mother would have walked beside her little boy. Maybe even held his hand. A happier little boy might have kept up with her better, or at least looked up to enjoy the sights around him. Of course, these are all just suppositions by the narrative of relations presented to us in this one snapshot of time. Clark might assume similarly, from the way he talks about how art is more than simply recording what the artist sees; instead, it involves stories told based on principles of selection, which itself “implies … a power to perceive relationships” (4). Clark would pick up on the distance and lack of connection between child and his mother, and we viewers do, too. Lange seems to suggest we should sympathize with this little boy who seems so sad. Lois in the Yakima Valley lived in a harsh, poor environment, but at least her mother’s watchful pose suggests love and care, as this mother’s stride ahead does not. To Lange, this small boy and his story matters—and her photograph makes him matter to viewers, too, as we wonder whether this is an isolated moment (did he just misbehave? Are they late for a doctor’s appointment?) or representative of his family life overall.

Figure 3. The Public Defender, Alameda County Courthouse, California. 1955-57.

Lange’s image titled The Public Defender, Alameda County Courthouse, California. 1955-57 features a different but also sympathetic subject (Figure 3). Part of a photo essay Lange put together that followed the daily work of public defender Martin Pulich, it was not widely circulated during her lifetime (Bullock). It depicts the top half of a man's head, cut off just below his nose; the lens focuses on the worry lines etched deep into his forehead. The man is in a low position looking up, though to whom—or what—we don’t know. This image invites viewers to imagine Foucault's "invisible realm" beyond the boundaries of the picture. Like the painter in Las Meninas, "[his] motionless gaze extends out in front of the picture, into that necessarily invisible region (Foucault 4). The lawyer is not looking at us, the viewers, but rather at something or someone beyond that we cannot see. Although his gaze is towards the camera, it is clear that instead of looking directly at us, he is seeing through us. It is as if we viewers are invisible watchers to a scene. The area behind us is outside our perspective, uncaptured by the camera's lens.

In this image, Lange’s title matters. Viewers only know that the man is at a courthouse because of the title, and we are left to wonder: What is it like? Who is on trial? What has the defendant done? Who is the lawyer looking at? And why is he so worried? However, unlike the mirror shown in Las Meninas, we have no window into what the answers may be. The lawyer's eyes are dark and unreflective of anything in front of him. Lange's choice of composition is also interesting here. Why did she cut off his mouth? Both his mouth, and what might be happening with it (is he talking?) leaves us to wonder at the unknown beyond what she captured. Mouths are very expressive, as they can show anger, distaste, happiness, or sadness. By cutting it off, Lange leaves us with only his eyes and those worry lines on his forehead to suggest his emotion. We are left to hypothesize the rest of the story, which suggests perhaps the narrative is the question. If everything is always contributing to the narrative as Clark says, then these invisible regions must be the narrative.

Lange seems to embody Benjamin’s point that especially in photography, an “authentic” print is no longer important, since art’s function “begins to be based on … politics” (6). Lange took photographs that did more than just record and preserve a moment in time; her composition choices inspired viewers to care about ordinary people and their situations. It was important that her viewers were often people with the power to make a difference, such as the U.S. government officials who saw her Yakima Valley photos and the law journal readers who saw her Public Defender series (Bullock). Lange’s body of work is featured today at MoMA, which honors its role as art. But recognizing how Lange’s composition choices could tug at the heartstrings of people who could make a difference, we are reminded that her art is also political.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, trans. by Harry Zohn, Schocken Books, 1969, pp. 1-26.

Bullock, River. “Written by Dorothea Lange: Magazine: MoMA.” The Museum of Modern Art, 26 Feb. 2020, www.moma.org/magazine/articles/245.

Clark, Kenneth. “Looking at Pictures.” Excerpted Class Handout from Looking at Pictures. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1960.

“Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures: MoMA.” The Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/5079.

Foucault, Michel. “Las Meninas.” Excerpted Class Handout from The Order of Things. Pantheon Books, 1970.

Gregory, Alice. “How Dorothea Lange Defined the Role of the Modern Photojournalist.” The New York Times, 10 Feb. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/10/t-magazine/dorothea-lange.html.

Meister, Sarah. “Pictures of Children.” The Museum of Modern Art, 24 Apr. 2020, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/294.

Whitney, Stephanie. “Part Two: Dorothea Lange in the Yakim Valley: Rural poverty and Photography in the Depression.” Dorothea Lange’s Yakima Valley Photographs, Pt. 2, Fall 2009, https://depts.washington.edu/depress/dorothea_lange_FSA_yakima.shtml.

Wilde, Oscar. “The New Aesthetics.” Excerpted Class Handout from Aesthetics. Oxford Press, 1998.

Figures Cited

Figure 1. Child and Her Mother, Wapato, Yakima Valley, Washington. August 1939. Lange, Dorothea. “Dorothea Lange. Child and Her Mother, Wapato, Yakima Valley, Washington. August 1939: MoMA.” The Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/collection/works/54400?/sov_referrer=artist.

Figure 1A. Child and Her Mother (2), Wapato, Yakima Valley, Washington. August 1939. Meister, Sarah. “Pictures of Children.” The Museum of Modern Art, 24 Apr. 2020, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/294.

Figure 2. Mother and Child, San Francisco. 1952. Lange, Dorothea. “Dorothea Lange. Mother and Child, San Francisco. 1952: MoMA.” The Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/54653?sov_referrer=artist&artist_id=0&page=4.

Figure 3. The Public Defender, Alameda County Courthouse, California. 1955-57. Lange, Dorothea. “Dorothea Lange. The Pubic Defender, Alameda County Courthouse, California. 1955-57: MoMA.” The Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/54130?sov_referrer=artist&artist_id=0&page=5.

Images sourced courtesy of ARTSTOR.

Copyright © 2021 Maddie Pintoff